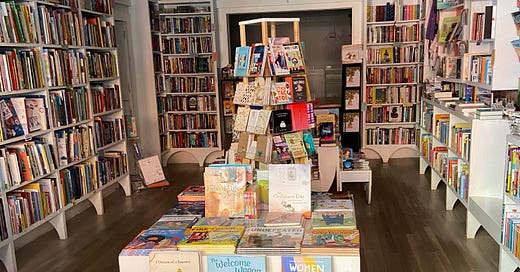

Two years ago today I locked the doors of Stories Bookshop + Storytelling Lab, my children’s bookshop + family gathering spot on Bergen Street in Brooklyn, and though we’d hang on in digital form for another year or so, never really opened them again to our community.

Perhaps like yours, my iPhone enjoys sending me daily photographic reminders of the days leading up to that day, reminding me, too, of the uncaptured moments, the sleepless nights that followed the days of packing up web orders— a crushing sense of responsibilities I might not be able to fulfill. What would happen to my staff? What would happen to my kids now that school was closed? Could I catch Covid picking up books to ship at the shop? What would happen to our family’s finances if we had to close completely? Where would I be, professionally? Would all the work and love we’d poured into Stories vanish, like it never was?

The photos make me cry, fill me with grief, still, though it was two whole years ago. It was such a scary time that it was hard to fully grieve the losses we faced. We were all in survival mode. If we started crying, we might never stop, the thinking went, and then how would we cope? There was zoom first grade to maneuver, and groceries to unpack with full body Clorox, there was the small business loan to pay off every month, there were so many people dying, so many doctors traumatized, there was New York City around us, hanging by a thread.

I’ve been thinking a lot about giving oneself permission to grieve, to mourn, to cry. As mothers with limited time to ourselves, how do we find the space? And as a culture of happiness junkies, how do we justify it to ourselves?

One year before the 2020 lockdown, I was in an even scarier position. In spring 2019 I almost died. I don’t talk about it much because it sounds so dramatic. The reason for that is because it was SO dramatic, but that doesn’t stop sounding so dramatic from being shameful and embarrassing. Also, the cause: my uterus was hemorrhaging, and like most women’s problems, even the barest bones summary, like the one in this sentence, is immediately TMI.

For weeks as I grew sicker and weaker, and was asked at the Emergency Room, where I went several times, if I would like to be admitted, I was bleeding a lot, but could probably also go home if I thought that was best, I said to myself, maybe it’s not that bad, which is what the experts also seemed to say.

The only reason I didn’t die is because one morning when I woke up and could not stand, and my face looked unrecognizable, and my children’s babysitter cried when she saw me, my husband called my doctor and said, Actually, it is that bad.

Even so, it was hard to believe, to trust, to insist on the urgency of my need. In the taxi on the way to the hospital I felt that peaceful lightness of letting go people who almost die describe, but when I got inside and they hooked me up to a machine in triage that read my heartrate, which was off the charts, the nurses looked at each other and one said, That can’t be right. The other one said, Actually, I think it is.

There it was, official data, and I was whisked inside to the concerned helpers, even though my need for help seemed so unlikely. The anesthesiologist was furious —how had something so treatable been allowed to get to this point? I was too weak, I couldn’t undergo surgery till I’d had a blood transfusion. My husband wept. They are finally listening, he said.

Still, I had a profound sense of not wanting to make a big deal. I didn’t want my kids to be scared. It seemed unseemly to make a fuss. Hysterical, as so many things uterus have long been labeled. Ungrateful, even. And after my surgery and transfusion, my physical recovery was swift. I took a couple days off and went back to work in the shop. I dressed up for family weddings. But my inability to say how bad it had been left me with trauma to work through. When I write about the experience, my heart still races. I’m still scared, three years later, thinking about it.

Two stories on grief and hardship in The New York Times last week stopped me in my tracks. One was on the DSM-5, the diagnostic manual for psychiatric treatment, being updated to include Prolonged Grief Disorder, defined as intense grief marked by pining and ruminating, lasting longer than a year. Two of the main changes wrought by this new diagnosis are financial: “clinicians can now bill insurance companies for treating people for the condition”; and pharmaceutical companies can develop and market new prescriptions to people who are doing grief wrong, for too long. This looks like toxic positivity in its most capitalistic incarnation. Parents who have lost children often don’t recover after a year. As one psychiatrist interviewed for the article says, “It just seems like you are pathologizing love.”

The other even more haunting Times story was first-hand accounts by Ukrainian mothers who had escaped their besieged homeland with their children, one of whom said, in spite of her harrowing journey out, and separation from her husband who remains to fight, and her loss of so much, “I pray all the time. But I don’t have the right to cry.” If not this woman, this week, who does have the right to cry?

I guess I’d argue we all do. Maybe we should all be crying a bit more.

Since my near-death experience (what a drama queen, writing those words) I’m highly sensitized to the way my friends disclaimer their troubles with phrases like, “at least I don’t…” or “I know it could be worse,” or “I’m so lucky that…”

Maybe it’s not really that bad. If such expressions offer comfort to anyone reading, hang on to them. We need all the comfort we can get. But if, like for me, they begin to feel like you are gaslighting yourself, and like such thinking might in fact be dangerous to your health and wellbeing, let’s try another tack.

We get this gaslighting from our systems—systems of white supremacy and patriarchy and capitalism tell us things as they are aren’t that bad. We’re over-reacting, and frankly being kind of a downer. Greta Thunberg still strikes for Climate every Friday while leaders continue to act like things, on a policy level, are not so urgent. Let’s not do the gaslighting to ourselves as well.

As my body healed in the summer of 2019, I started to see a therapist who recommended the simplest treatment of all: crying. She said if I couldn’t find much time for myself without my kids around, to just steal away in my car for ten minutes and play a sad song. That crying was the most amazing release—a form of our body’s natural intelligence. That by not grieving my grief I would also not feel my other feelings —you can’t selectively block one emotion without blocking all the others so in order to truly feel the daily joys you have to truly feel the daily losses. So, I cried, in brief, potent episodes.

I’m still crying. The end point is not no crying. I’ll be crying from here on out. Just a little every day. And honestly feeling a little bolder every day, too.

Because what if we’ve been trying to cope wrong, holding it in, just getting over it, not crying because things could be worse, we don’t want to scare or trouble anyone, not grieving too much as to be hysterical or disordered. What if our stoical coping has served the interest of someone other than ourselves? And someone other than the most vulnerable among us, who most need our care? And benefiting something other than our planet? What if we allowed ourselves our daily weep, let ourselves really wail, even if it’s only for ten minutes, listening to that sad song on the radio?

Because what if feeling the full grief and trauma of our losses is the thing that will finally inspire us to save ourselves and each other after all?